2.1 Frequency

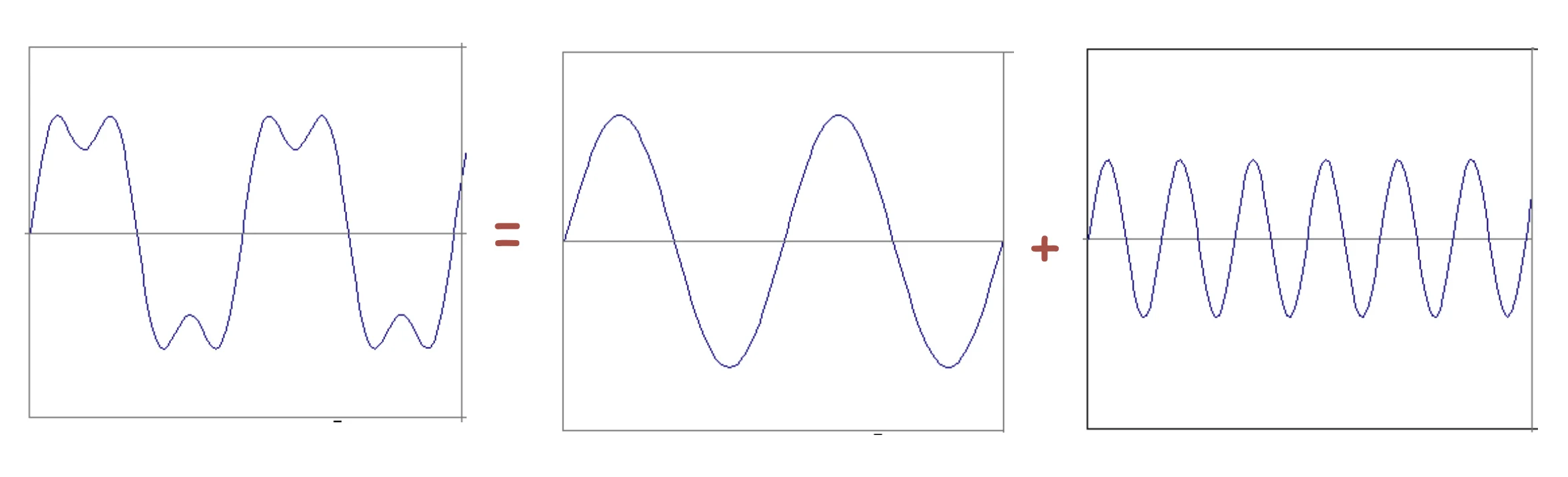

A sum of sines

Building blocks:

Frequency Spectra

Example

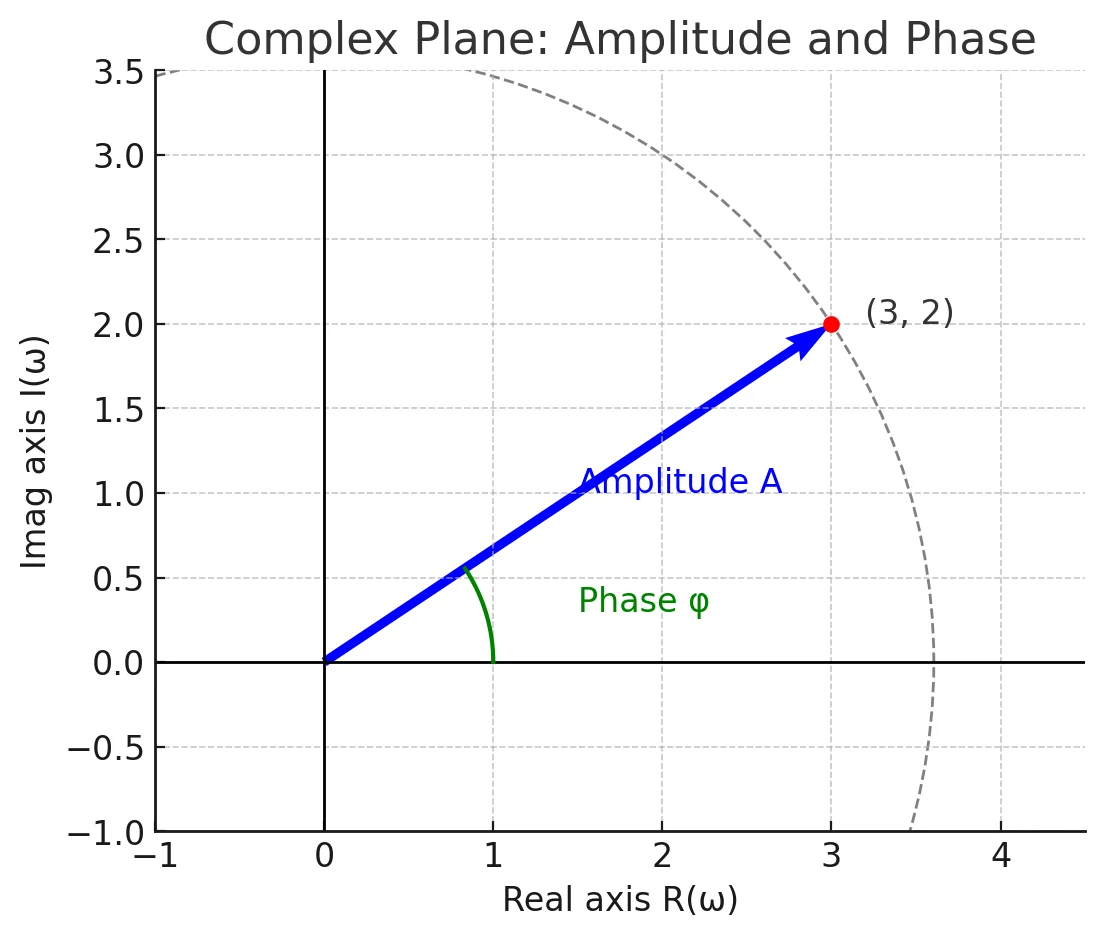

How to construct a square wave

- Add enough of these signals

at decreasing amplitudesas youincreasethefrequencyof this sinusoid. Then, the sum of signals converges to asquare wave

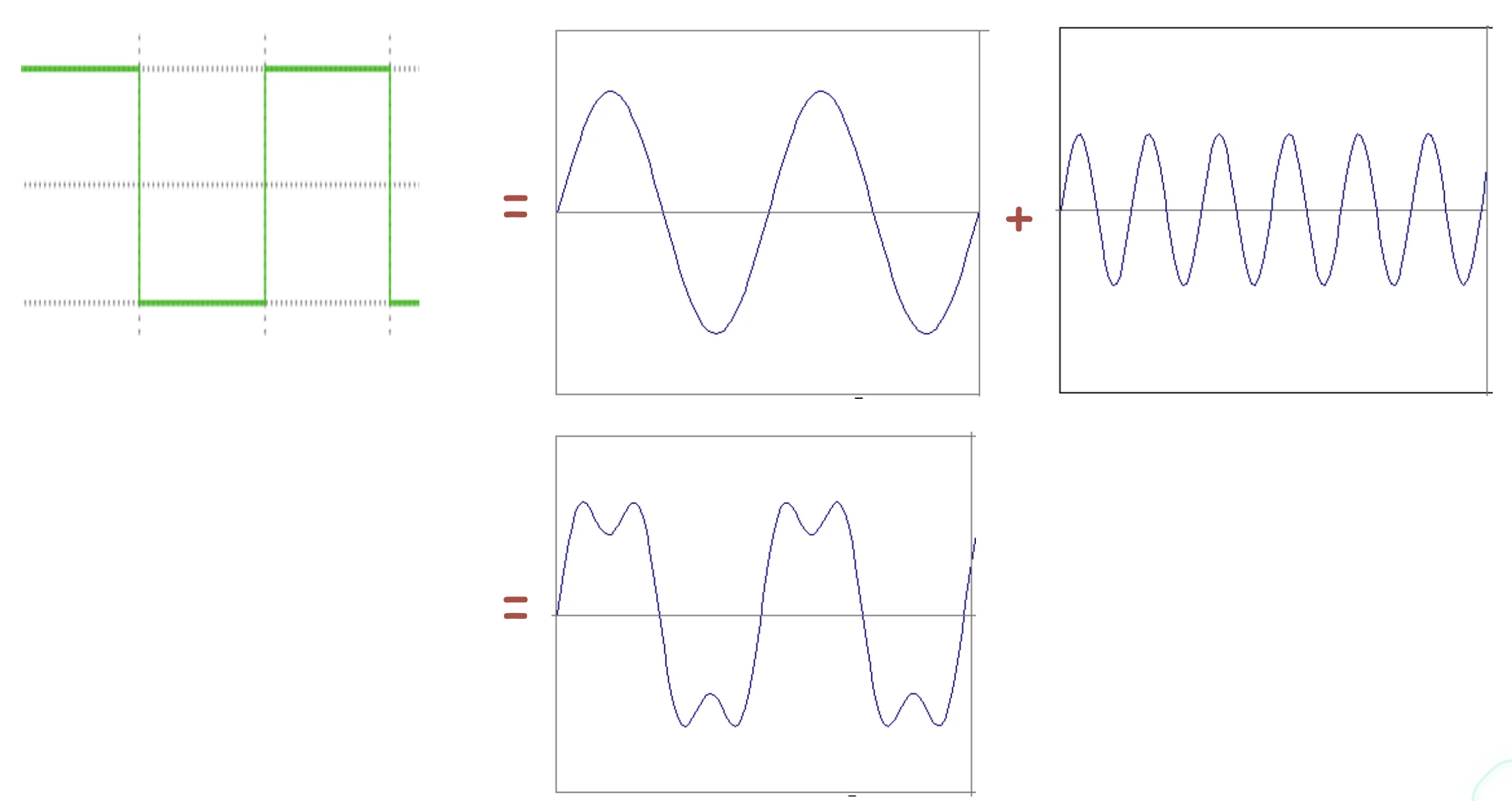

Fourier Analysis in Images

Fourier Transform

-

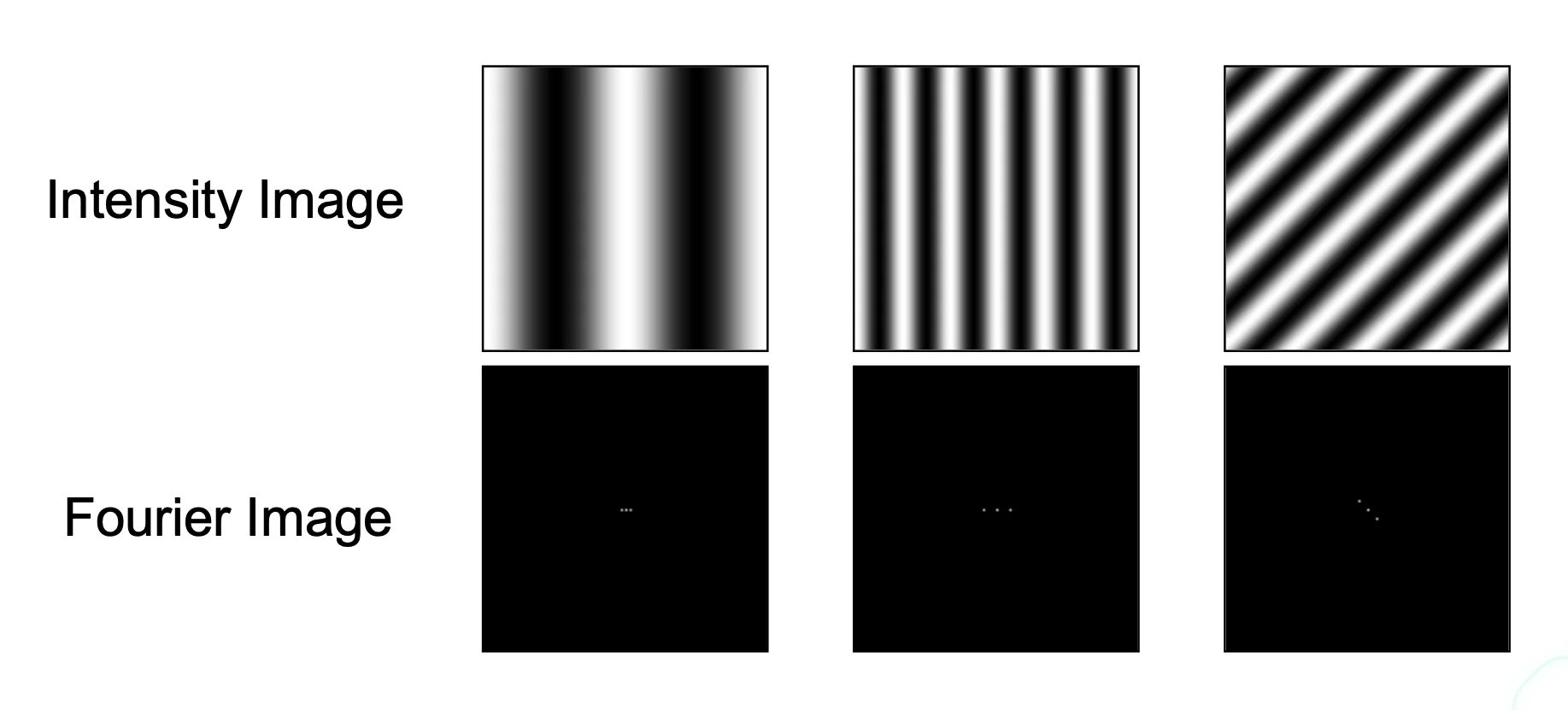

Fourier transform stores the

amplitudeandphaseateach frequency -

Amplitude: encodes the number of signals at a particular frequency -

Phase: encodes spatial information

1. Amplitude Formula

where:

-

: the real part of a complex function (often a Fourier transform).

-

: the imaginary part.

-

: a complex number representing a signal at frequency .

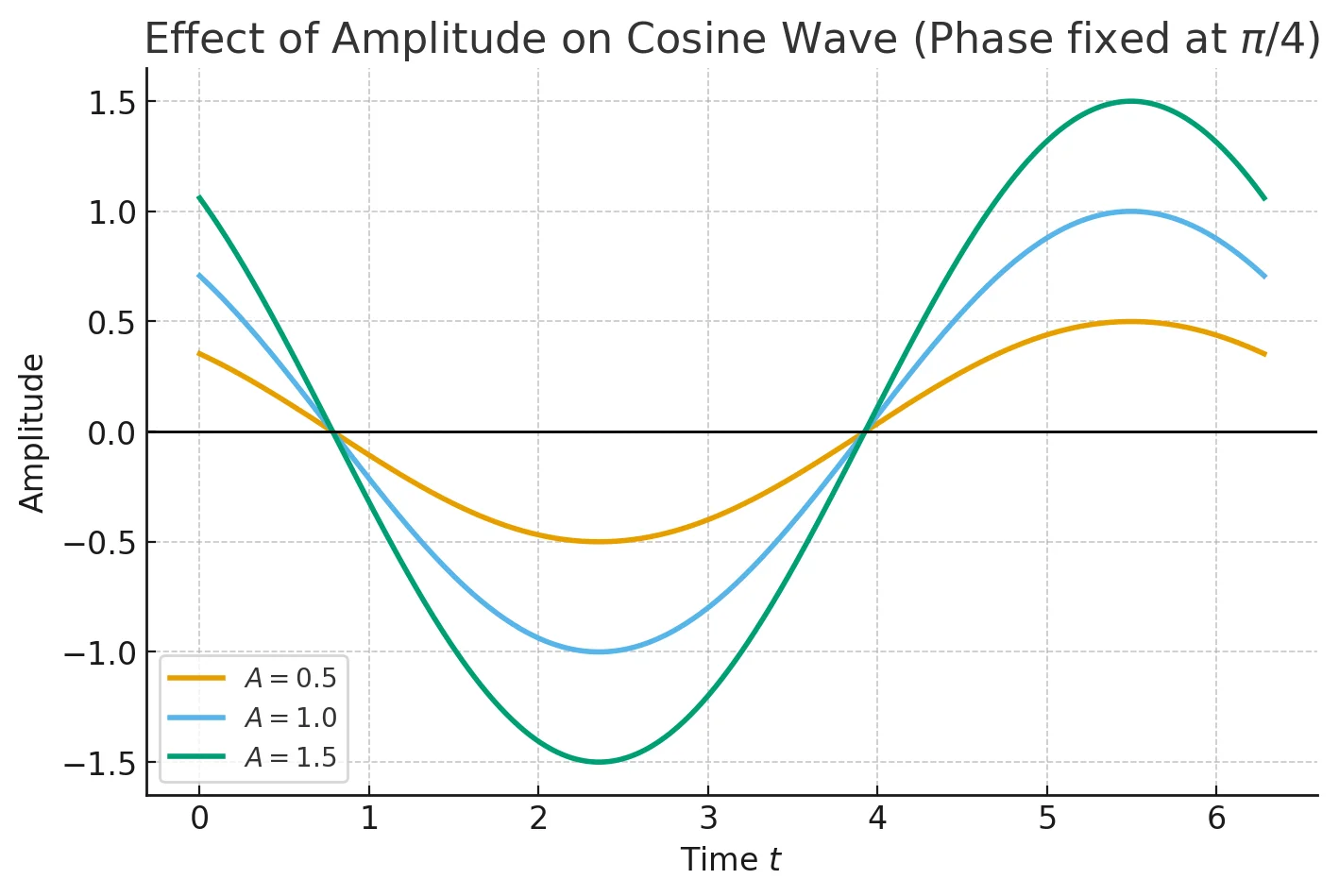

Amplitude on Cosine Wave

# Time vector

t = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 500)

# Parameters

omega = 1.0 # frequency

phi = np.pi/4 # fixed phase

# Different amplitudes

A1 = 0.5

A2 = 1.0

A3 = 1.5

# Signals

y1 = A1 * np.cos(omega*t + phi)

y2 = A2 * np.cos(omega*t + phi)

y3 = A3 * np.cos(omega*t + phi)

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(8,5))

plt.plot(t, y1, label=r'$A = 0.5$', linewidth=2)

plt.plot(t, y2, label=r'$A = 1.0$', linewidth=2)

plt.plot(t, y3, label=r'$A = 1.5$', linewidth=2)

Note

The amplitude (or magnitude) is just the length of this complex number in the complex plane. Pythagorean theorem:

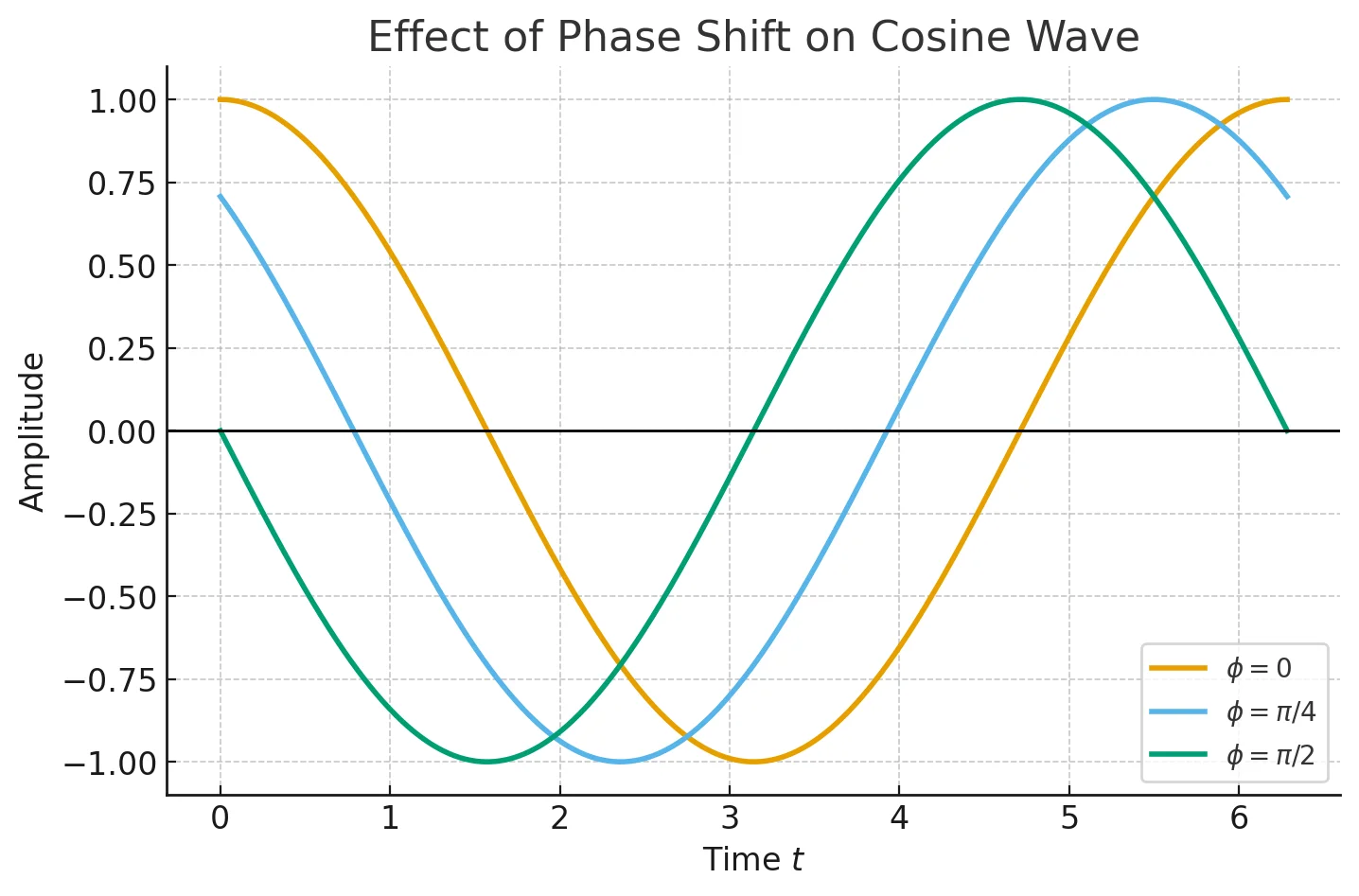

2. Phase Formula

-

The phase angle describes how much the sinusoidal signal is shifted horizontally relative to a cosine (or sine).

-

In the complex plane, the phase is the angle made by vector with the positive real axis.

Shift on Cosine Wave

# Time vector

t = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 500)

# Parameters

A = 1.0 # amplitude

omega = 1.0 # frequency

# Different phases

phi1 = 0

phi2 = np.pi/4 # 45 degrees

phi3 = np.pi/2 # 90 degrees

# Signals

y1 = A * np.cos(omega*t + phi1)

y2 = A * np.cos(omega*t + phi2)

y3 = A * np.cos(omega*t + phi3)

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(8,5))

plt.plot(t, y1, label=r'$\phi = 0$', linewidth=2)

plt.plot(t, y2, label=r'$\phi = \pi/4$', linewidth=2)

plt.plot(t, y3, label=r'$\phi = \pi/2$', linewidth=2)

Note

In practice, we often use atan2(I, R) instead of, because atan2 takes into account which quadrant the point lies in (avoiding sign ambiguities).

3. Euler’s Formula

-

Exponentials with imaginary exponents represent rotations in the complex plane.

-

The real part gives a

cosine, and the imaginary part gives asine.

So when we write:

-

: the amplitude (the radius in the complex plane),

-

: the phase (the angle).

Tip

The derivation is shown in Euler’s Formula

Integration and Fourier Transform

Important

Imaginary number is presented with due to mathematical convention

General Form

- : Fourier Transform

- : frequency domain

Continuous Fourier Transform (CFT)

used when is a continuous signal

- projects the singal onto complex exponentials

- At each frequency , it computes the amount of that frequency is present in the singal

Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT)

used when is a discrete signal

where:

- : the number of samples

- : frequency index (integer)

- cycles through different frequencies, checking how much of each frequency is present

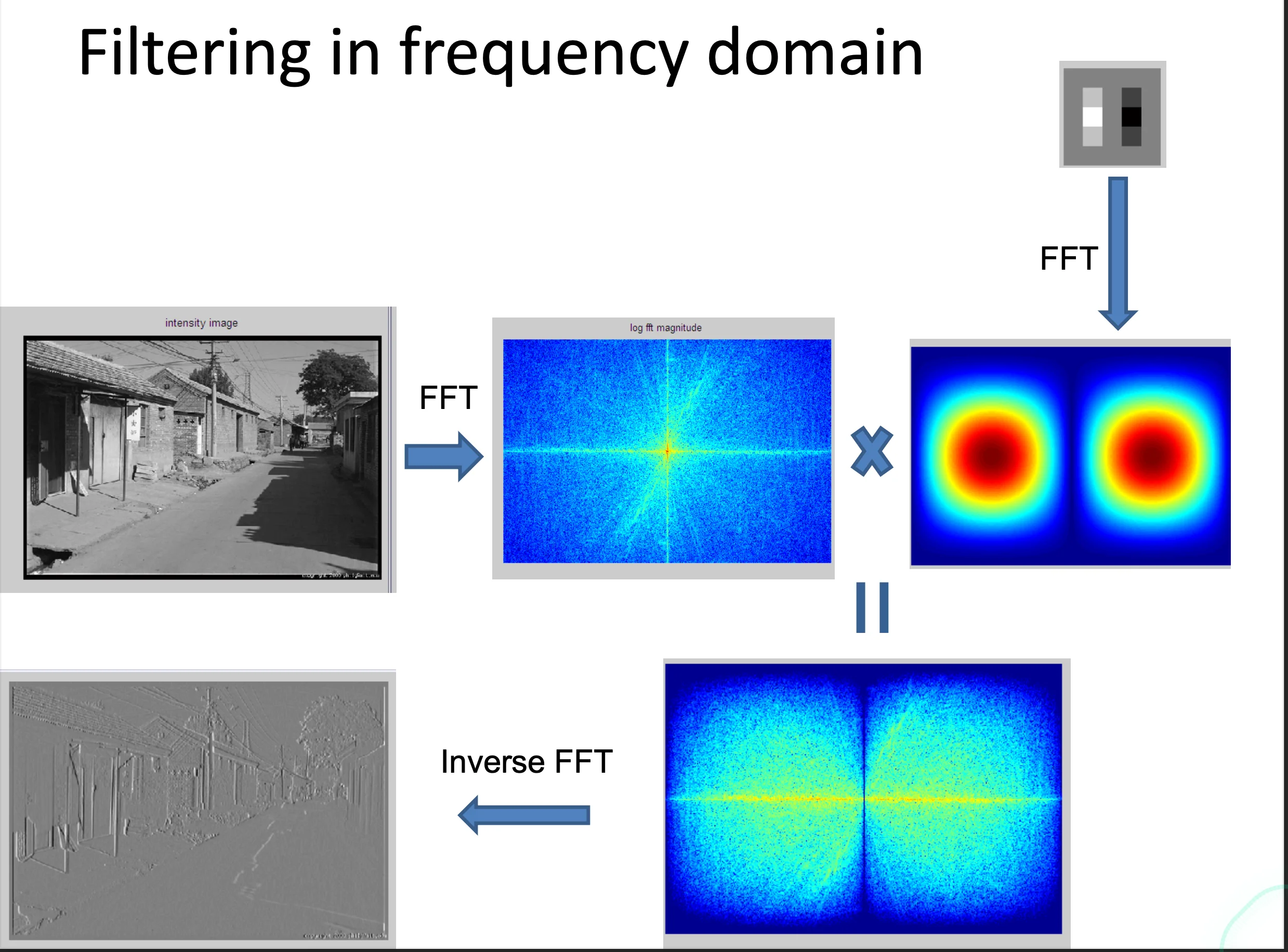

The Convolution Theorem

- The Fourier transform of the convolution of two functions is the same as the product of their Fourier transforms

- The inverse Fourier transform of the product of two Fourier transforms is the convolution of the two inverse Fourier transforms

Important

- Convolution in the spatial domain is the same as the Multiplication in the frequency domain

- FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) can convert between the spatial domain and frequency domain in with being the number of pixels

Properties of Fourier Transform

- Linearity

- Fourier transform of a real signal is symmetric about the origin

- The energy of the signal is the same as the energy of its Fourier transform

- You don’t lose information when you convert back and forth between spatial and frequency domains

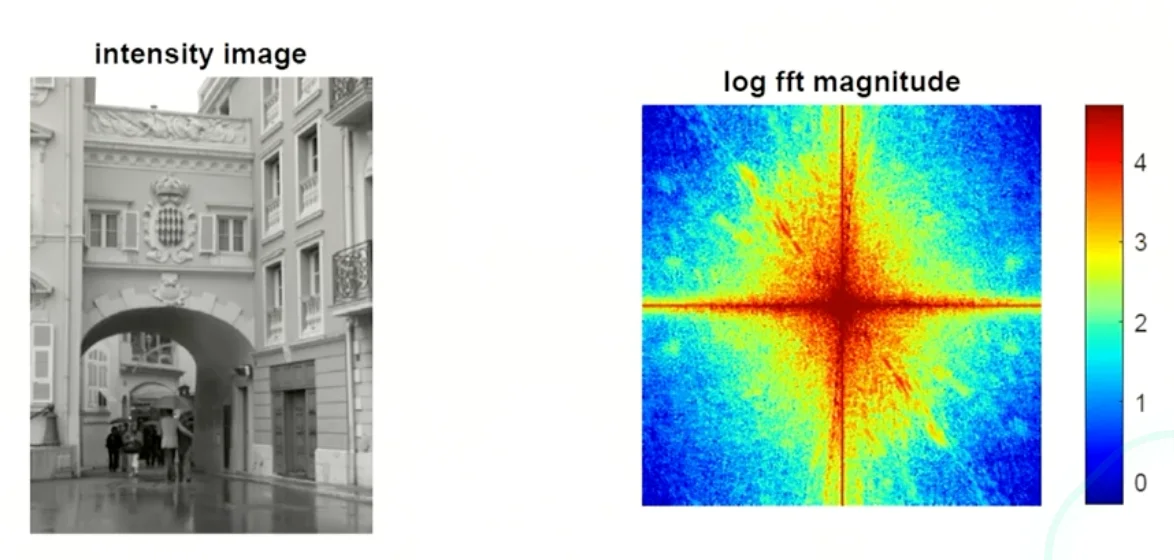

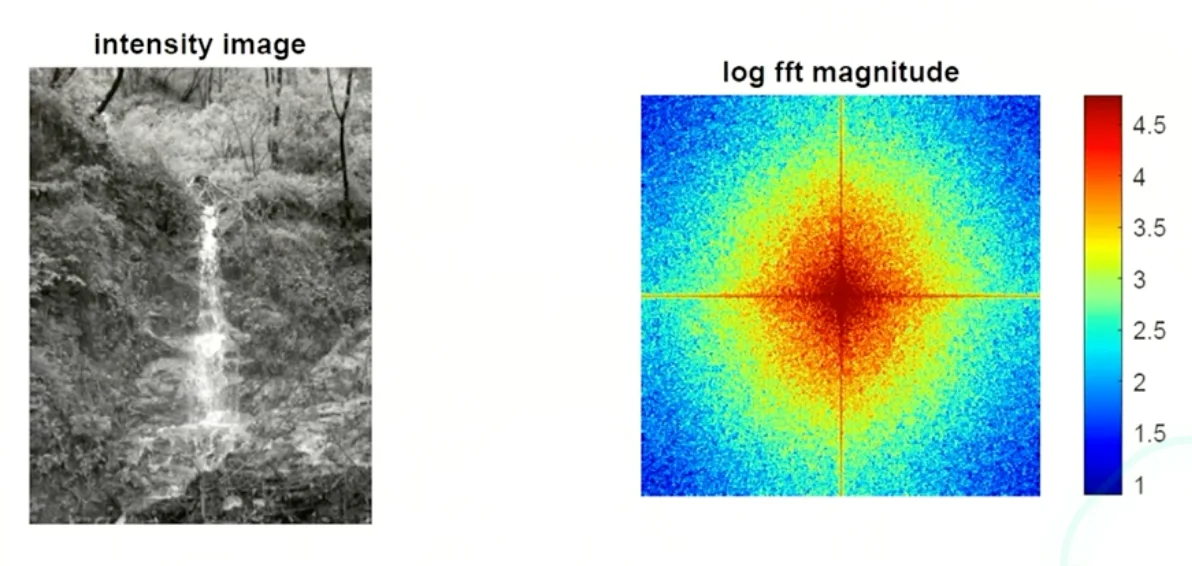

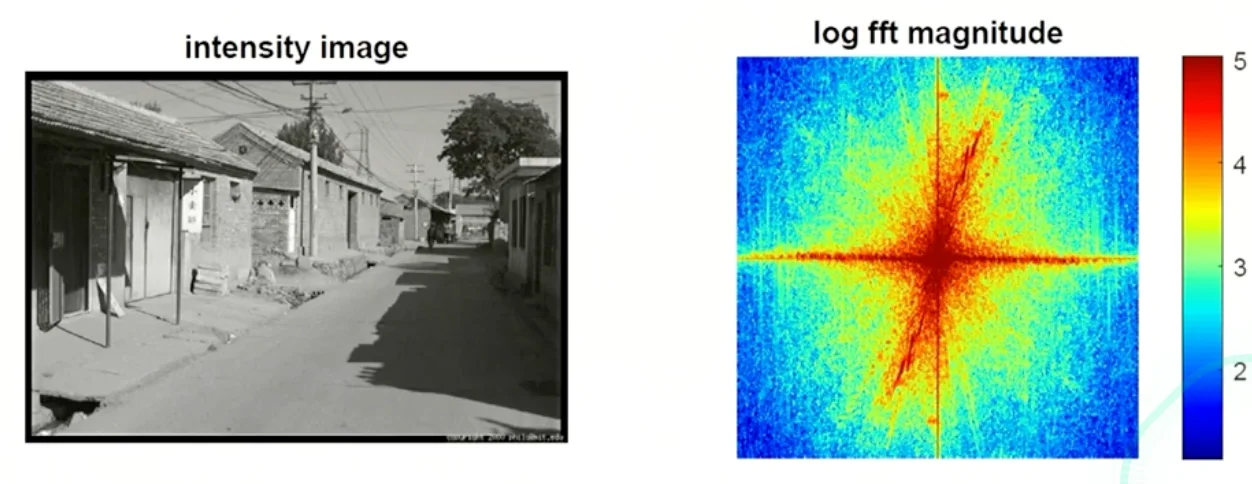

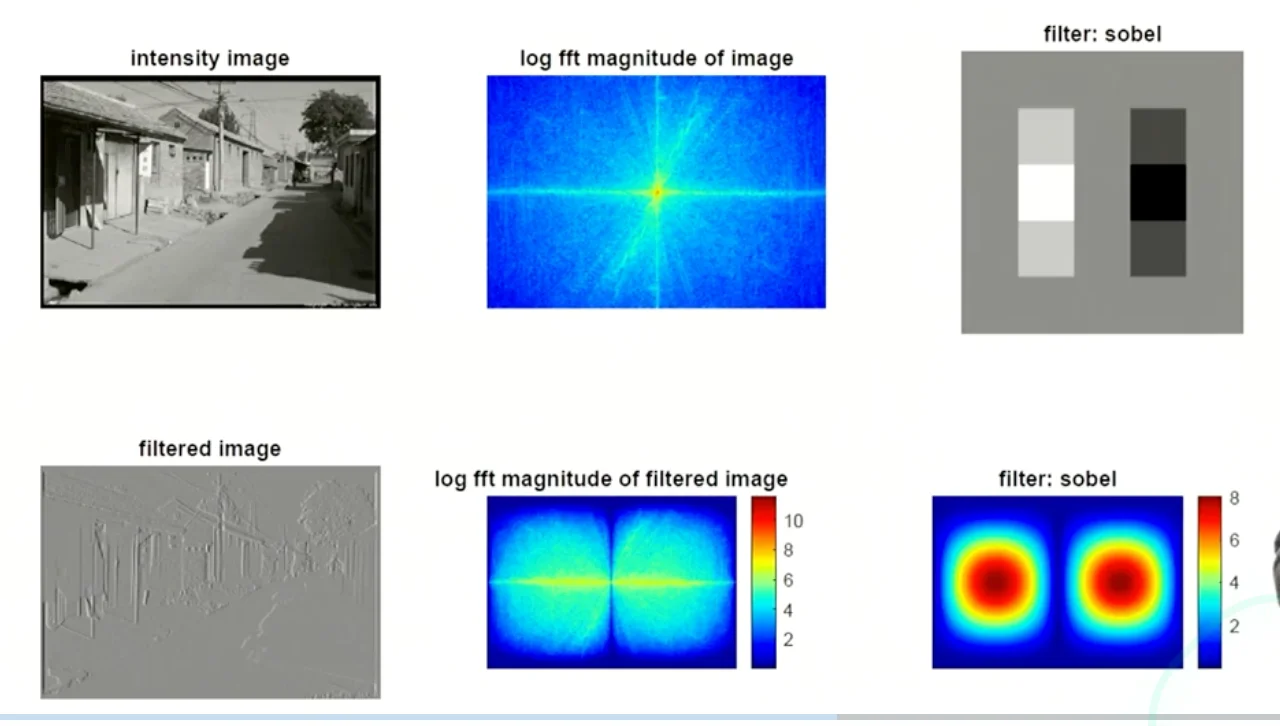

Image Frequency Examples

- Frequency changes

- Moving horizontally and vertically crosses a lot of edges.

- Frequencies are spread evrywhere more rounded

Note

For city images it’s more common to have star shapes, while natural images are tend to be rounded shapes.

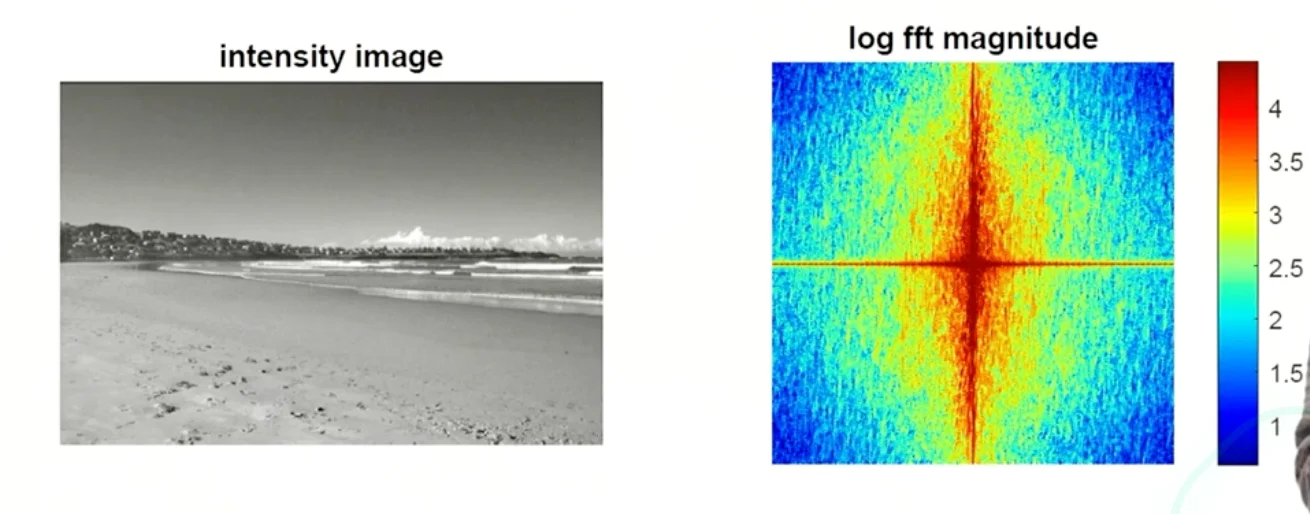

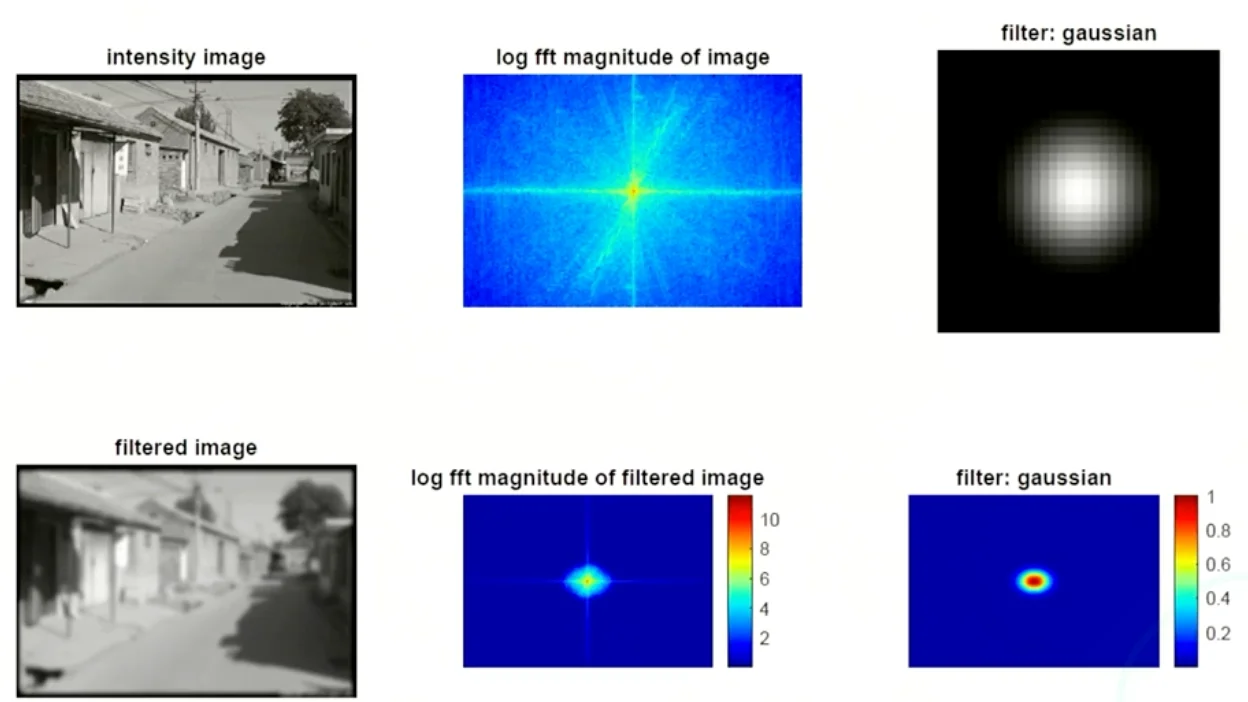

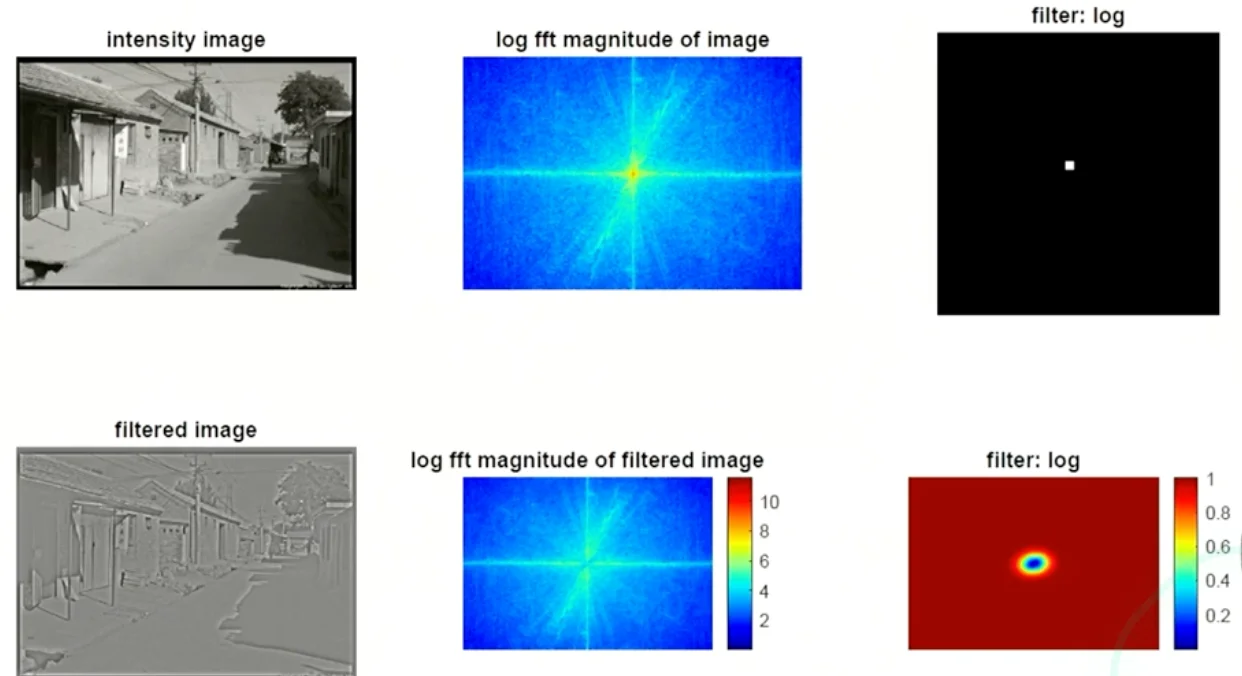

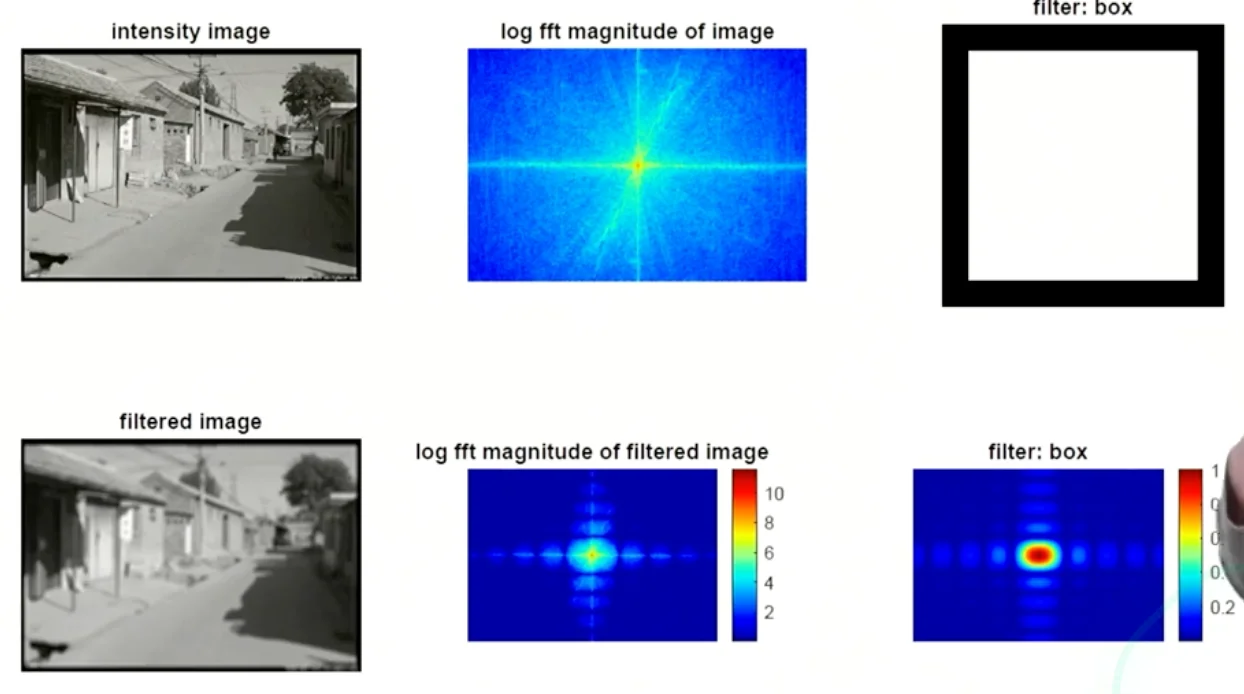

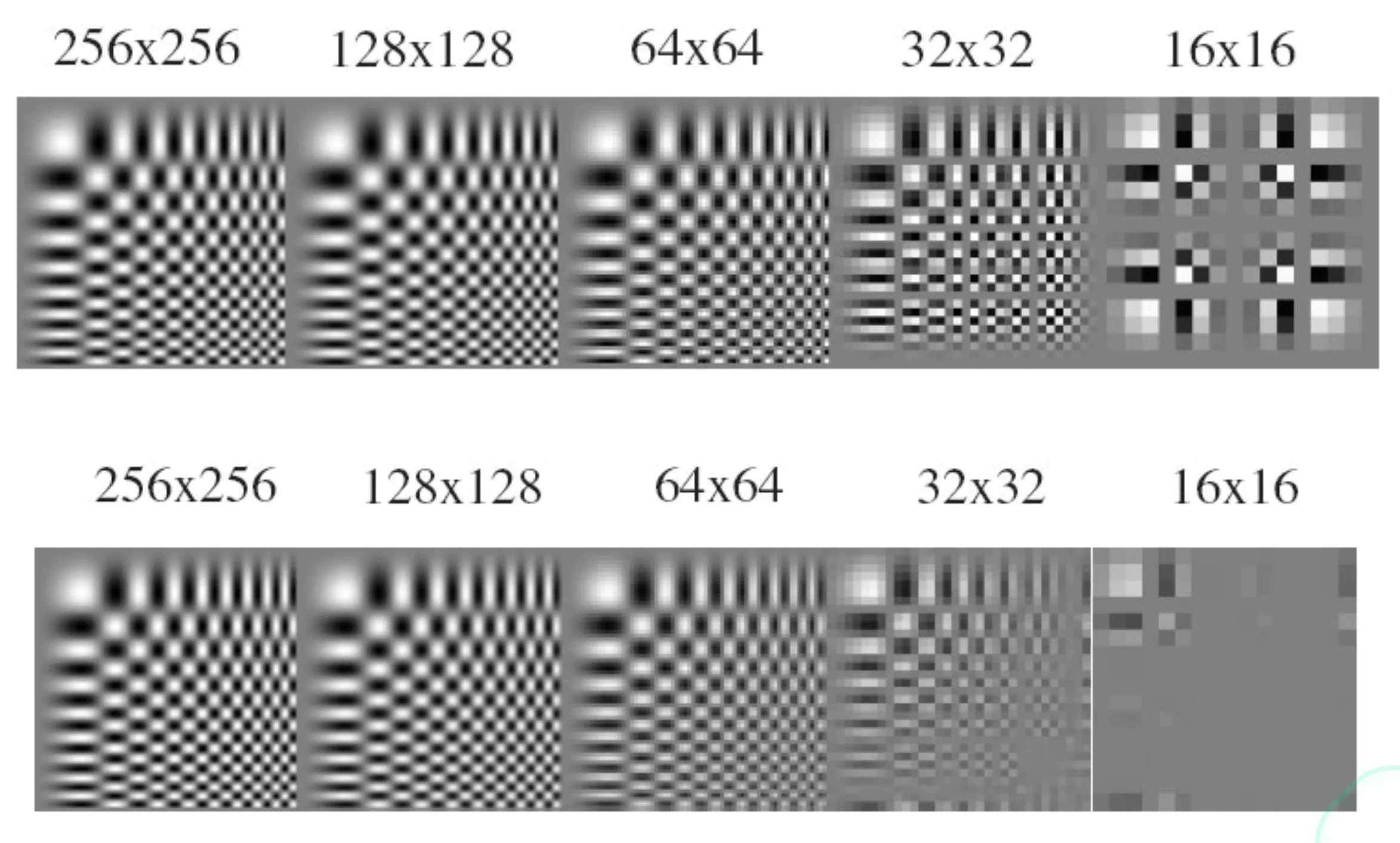

Comparison of filters

- Gaussian filter selecting for lower frequencies

- Box filter:

- preserve both low and high frequencies

- The disjointed range of higher frequencies is also preserved, so it doesn’t prove as good of a smoothing effect as a Gaussian

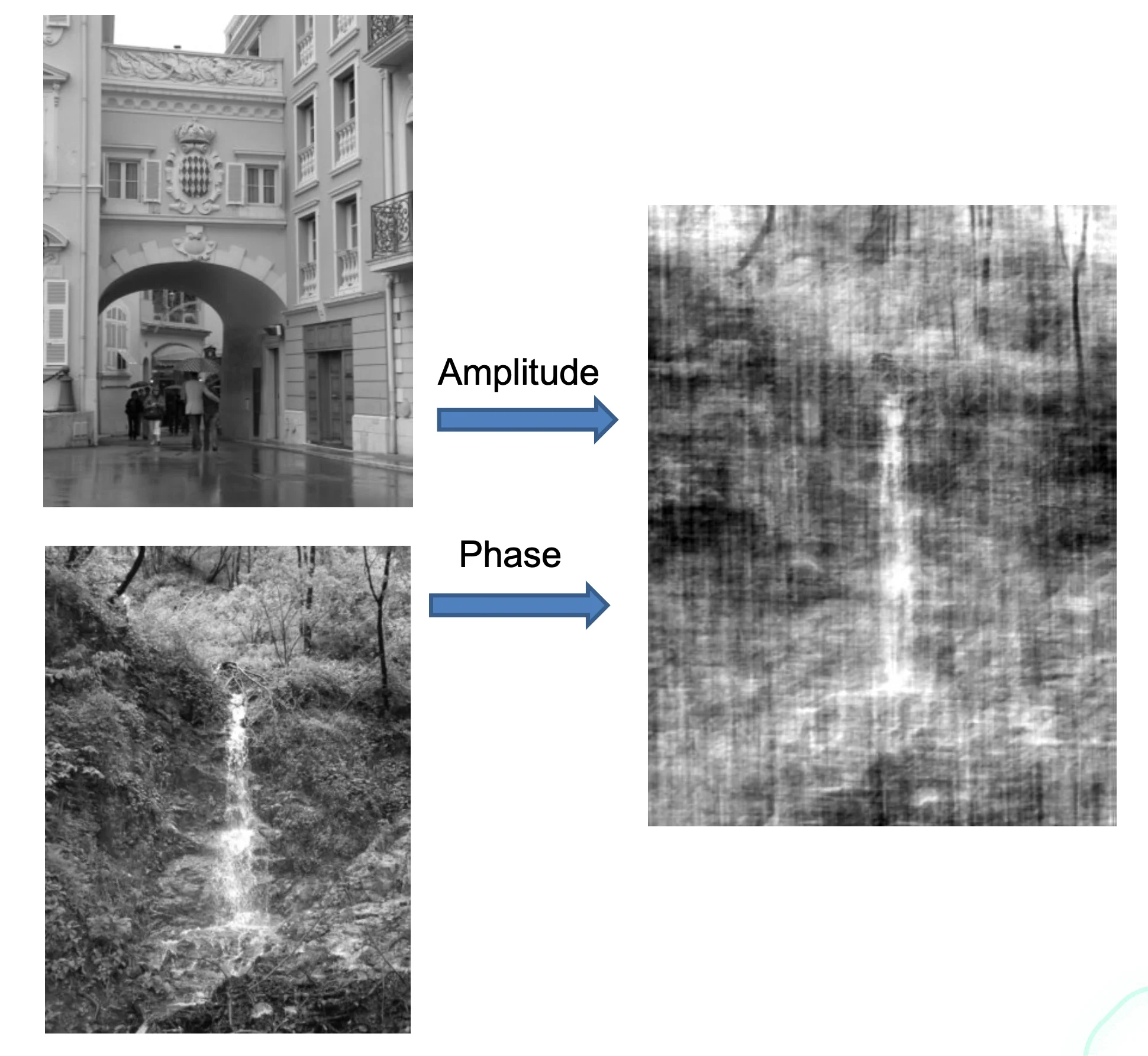

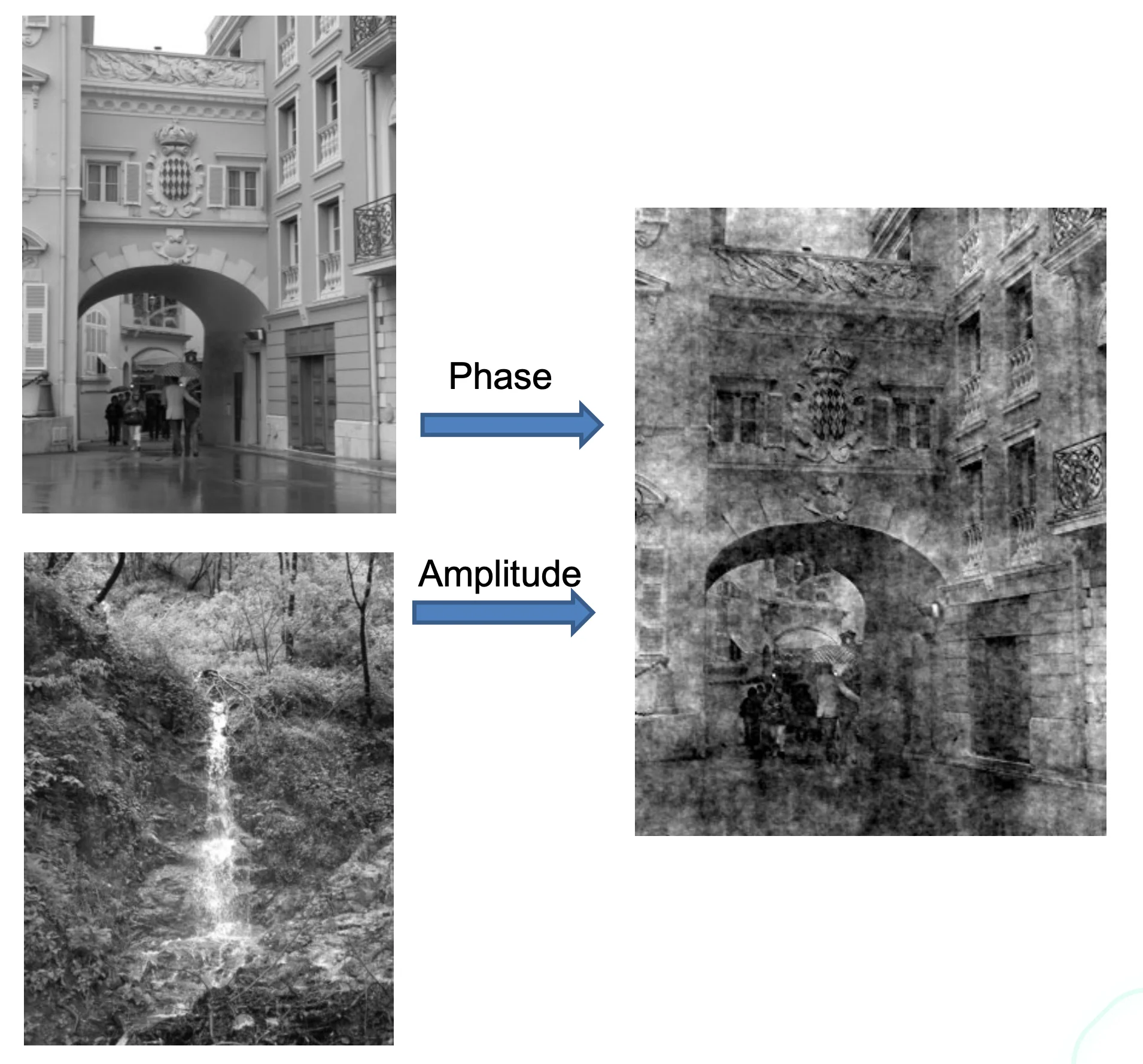

Mixing Images

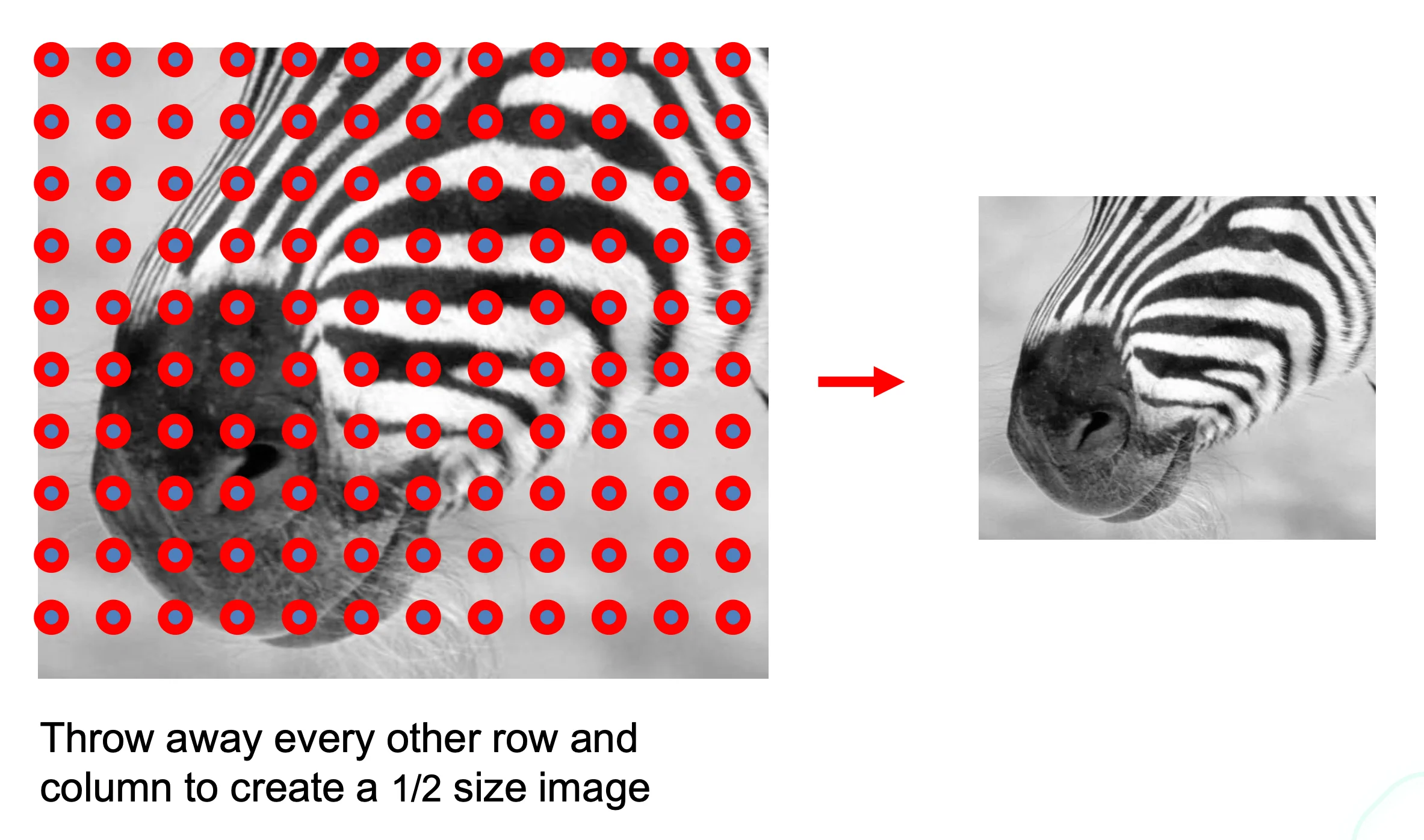

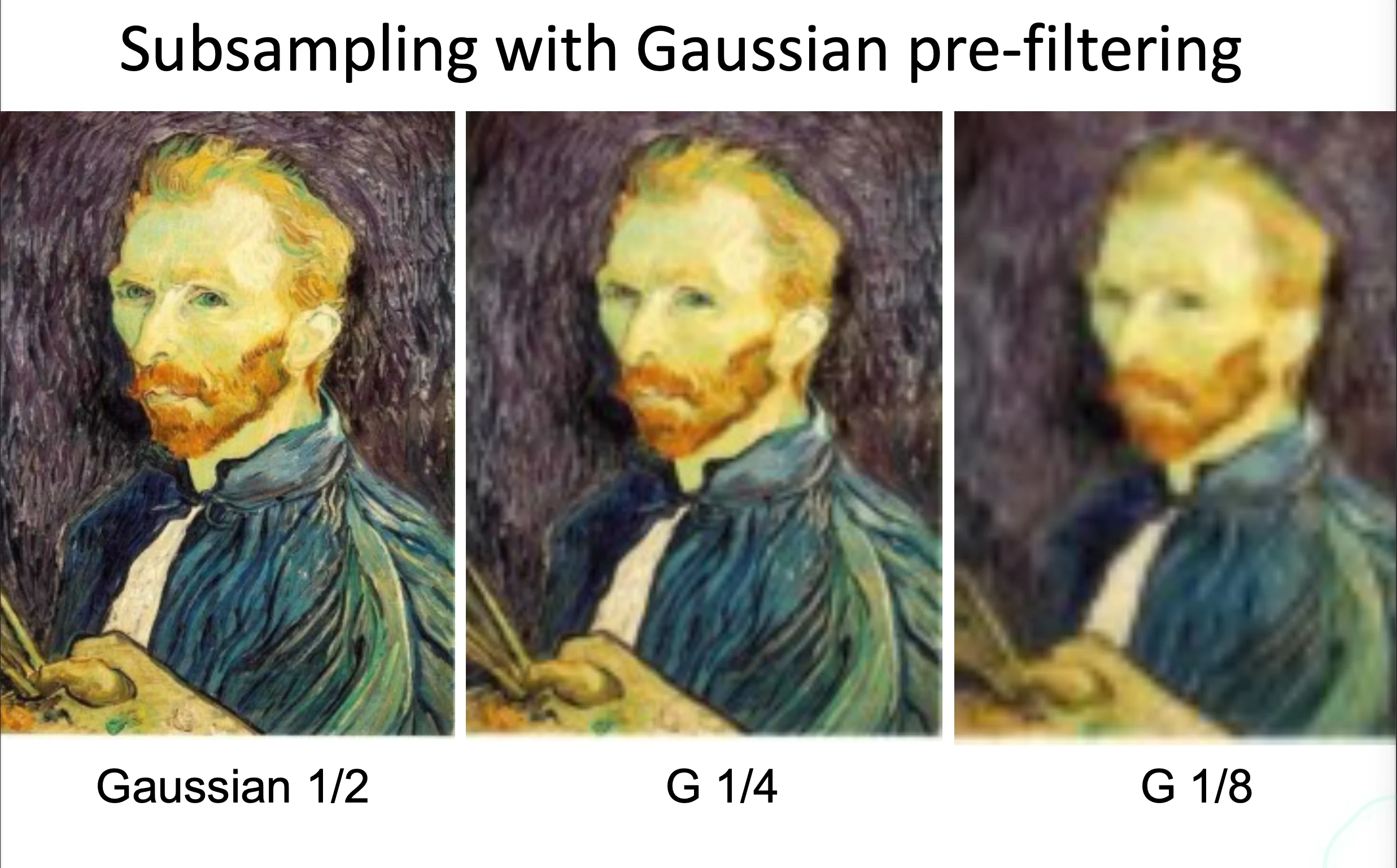

Sampling

- Why does a lower resolution image still make sense to use?

- Images are typically smooth, and sampling cuts off high frequencies, which are not that many in a image

- We can thus shrink an image without losing a lot of information

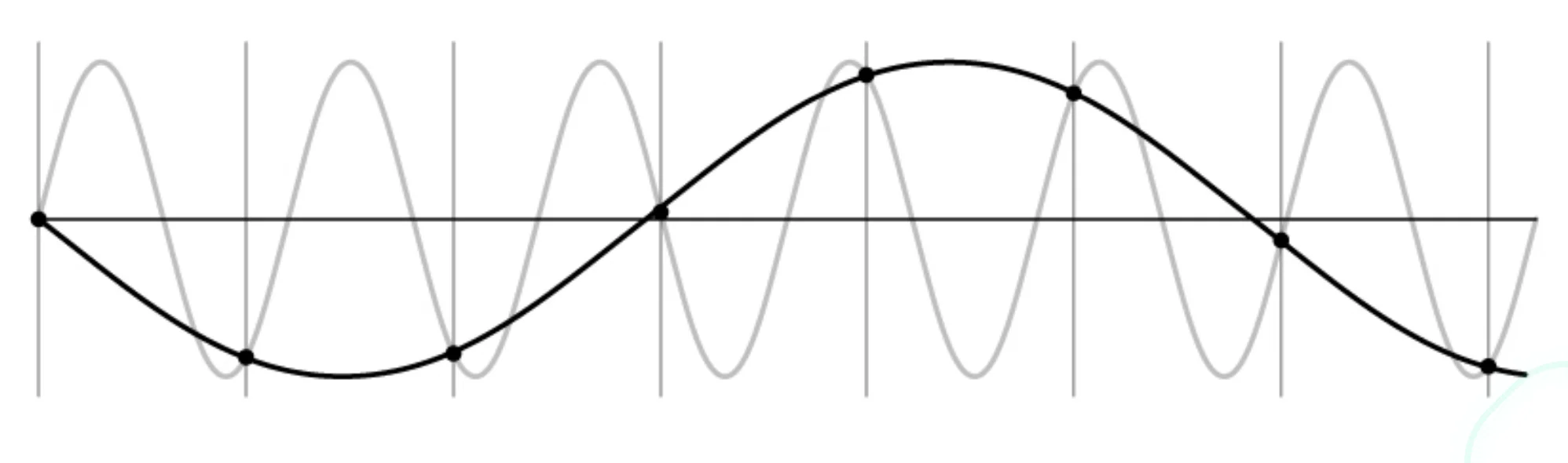

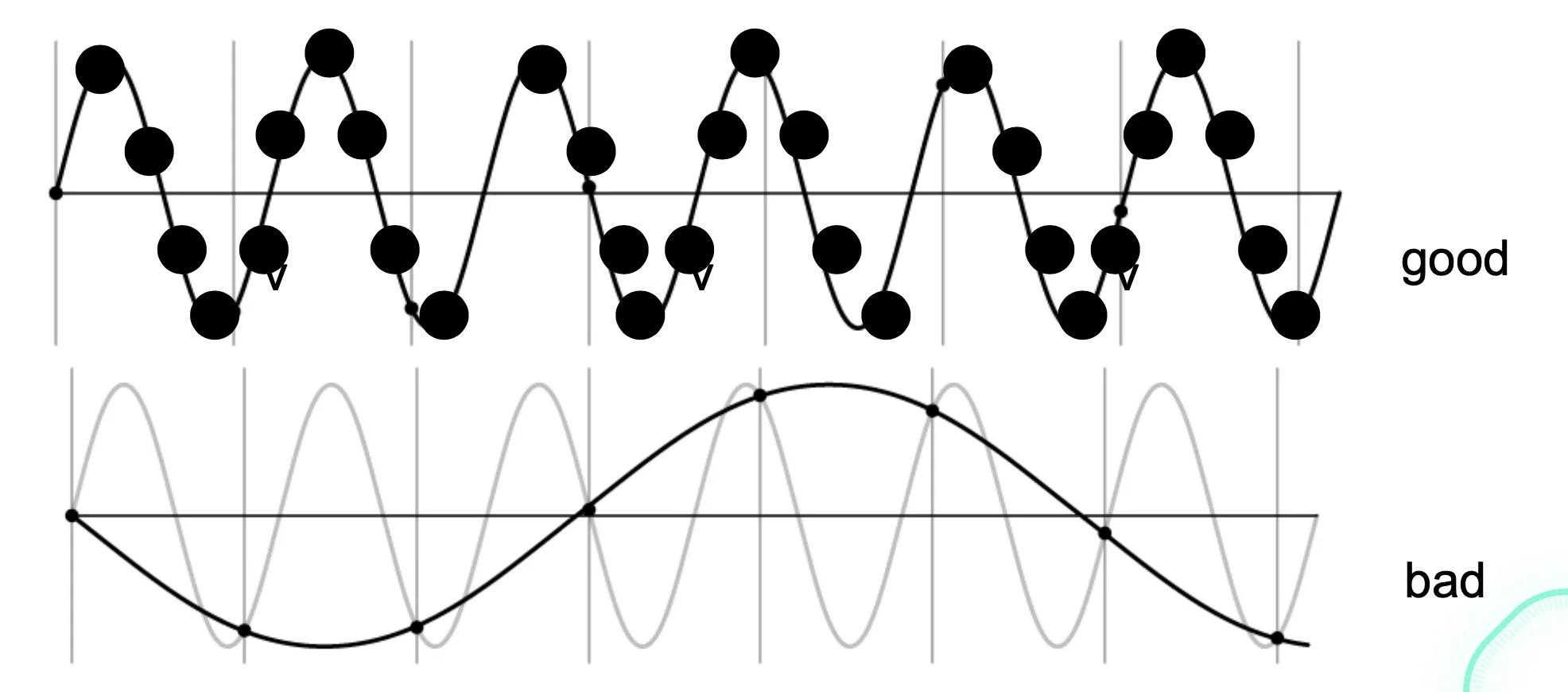

Aliasing Problem

- Sub-sampling may be dangerous as characteristic errors may appear

- We create an artifact that’s not in the original signal

Nyquist-Shannon Sampling Theorem

- When sampling a signal at discrete intervals, the sampling frequency must be

- : max frequency of the input signal

- This allows a reconstruction of the original image

Solution (Anti-aliasing)

- Sample more often

- Get rid of all frequencies that are greater than half of the new sampling frequencies

- lose some high frequencies information but it’s better than aliasing

import numpy as np

from scipy.ndimage import gaussian_filter

# 1. Start with image(h, w)

# Let's assume `image` is a NumPy array of shape (h, w)

# 2. Apply low-pass filter (Gaussian blur)

im_blur = gaussian_filter(image, sigma=1) # fspecial('gaussian', 7, 1) ≈ Gaussian with σ=1

# 3. Sample every other pixel

im_small = im_blur[::2,::2]

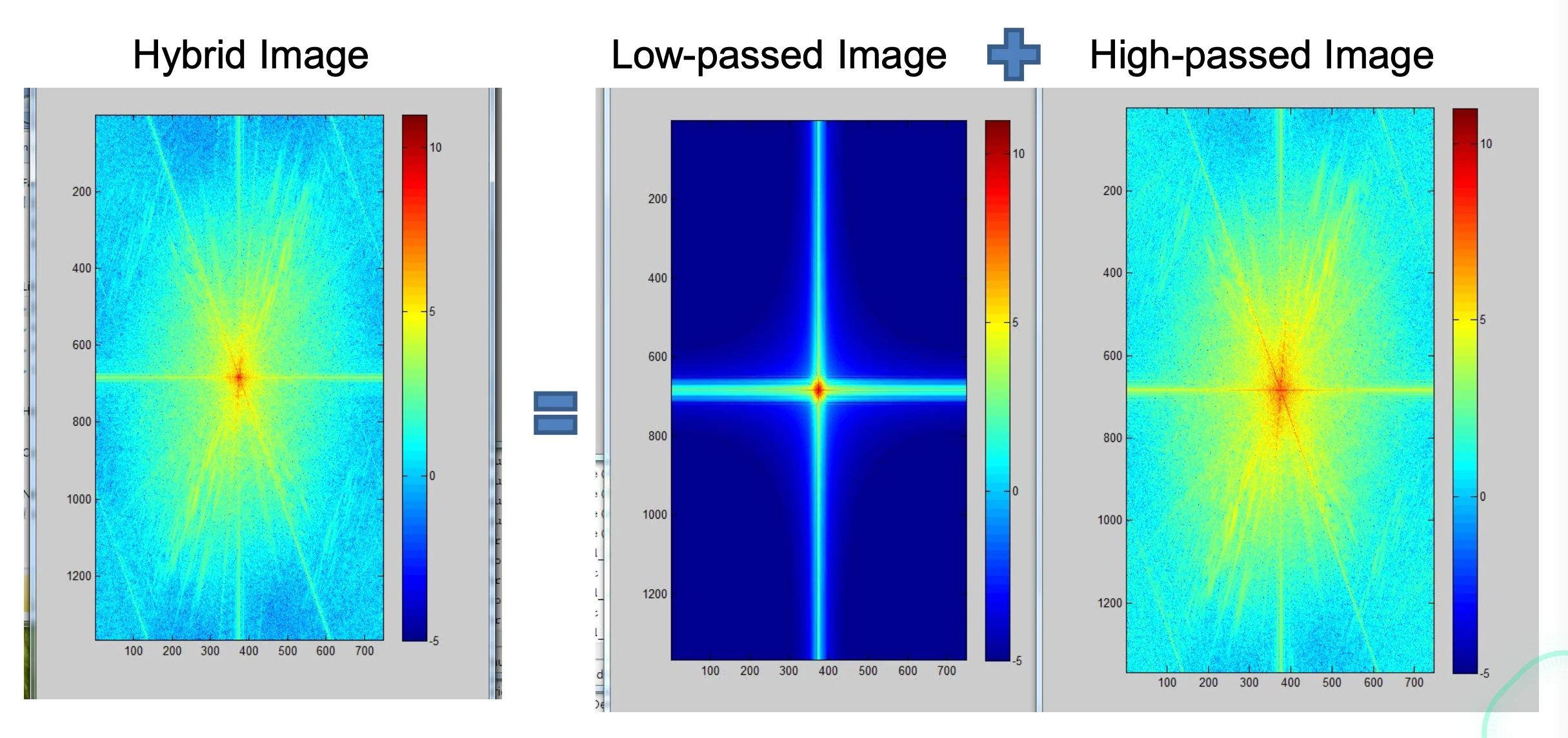

Hybrid Image in FFT

- When we’re close to the image, the higher frequencies dominate our perception, so we observe them much more readily

- When we’re further away, high frequencies are smoothed out and we can only observe the low passed image